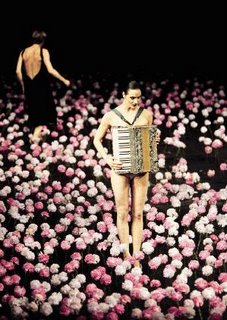

I was in NYC over the weekend. On Saturday evening, we went to BAM to see Pina Bausch's Tanztheater Wuppertal and her piece "Nefés" (here's the NY Times review).

I was in NYC over the weekend. On Saturday evening, we went to BAM to see Pina Bausch's Tanztheater Wuppertal and her piece "Nefés" (here's the NY Times review).It was a lovely piece, but, as the review points out, much less theatrical than Pina Bausch's earlier choreography and more focused on the dance itself. It struck me as a move away from the kind of contemporary dance that "Pina" pioneered.

One way to view the history of Western dance is as a history of placement of the human body's axis. It's an unflattering analogy for contemporary dance, but think of that image of human evolution in which homo sapiens develops from primates and australopithecus through gradually rising hominoid ancestors, with the final image being the man, upright, impaled on the vertical axis. The history of Western dance, at least from ballet to contemporary dance, involves the converse evolution.

Ballet is almost entirely vertical. The body stretches this verticality as far as possible. Thus, the height and length of the dancers, the pointe, the pirouette, the entrechat, the notion of ballon, even the arabesque, all movements in ballet that extend the body upon its vertical axis or hold it aloft. Ballon is weightlessness in the execution of a jump, a vertical perceptual extension beyond the limitation of gravity. The beauty of ballet is a function of the gracefulness and power with which this vertical rigidity is maintained. There remains a tension between the constraints of the rigid vertical axis and movements that suggest an aesthetic of symmetry and transcendence.

Modern dance - perhaps especially the free dance of Ruth Saint-Denis - asked why this verticality should be considered the essence of beauty in the movement of the body. The modern experiment became one of rotating the axis, creating diagonal forms and movements. The vertical axis remained, but was supplemented with other movements. The tension around ballet's axis was relaxed. Martha Graham, for instance, was known for the principle of contraction and release where the body "breathed" inward in order to "exhale," or open beyond the simple line of the spine. The movement was one of a slow unfolding of the body from its living, breathing center. Movement was liberated from ballet's rigidity and the result neatly paralleled developments in modern painting. Graham's choreography had a close relationship with abstract expressionism as well as with other artwork that critiqued orthodox notions of beauty and form, such as Isamu Noguchi's sculpture (and set designs for Martha Graham). Merce Cunningham, a Graham prodigy, relied on chance to choreograph movements, working with John Cage's musical experiments.

Contemporary dance, however, found formal constraints of modern dance perplexing and generally moved further towards improvisation. Modern dance had not gone far enough in reconceptualizing the body's axis. In ballet, the axis was vertical. With modern dance, the axis rotated. But what if the entire notion of axis was reconceptualized? Modern dance had already imported elements from theater and elsewhere, but contemporary dance, especially in the very different versions developed by Pina Bausch and Japanese butoh, redefined the axis altogether.

Pina brought in theater, choosing dancers as much for their comedic skills as their ability to move. She brought humor to the performances. There was no need to remain dour and austere about the movement of the body. Now the axis became not only the very limits of bodily movement, but also the intellectual and emotional life of the body of each dancer. Whereas in ballet, dancers were largely disposable except for those with the most perfected technique, now, in contemporary dance, the imperfections and variety of human bodies, emotions, intellectual life became the axis itself. Dance became embedded in actual experience, rather than attempting to transcend experience through the heaven-seeking vertical axis. This also meant, given the international background of her dancers, that their own contexts came to the fore in performances.

Abstraction, linear stories, folk songs, jokes, music, seductions, acts of violence, movements imported from daily life and from the history of dance, and the bombast of cabaret were all resources for contemporary dance. In Tanztheater, these might be strung together with a kind of story or not. Pina's works do have consistent themes, one of them being the intricacies and comedic theatricality of romance and seduction between human beings. There's quite a bit of the primate in such human rituals.

These themes remain in "Nefés" (2003). But her work has also moved away from theater and more towards expressive movement. In this sense, the personalities of the dancers are internalized. Their histories are performed by movement more than through the more explicit means of storytelling we're usually accustomed to. Oddly, this pushes the work back in the direction of modern dance by returning to the rotating axis of the body. But it also, very subtly, gives the axis a complex and rich history of Pina herself and of her dancers as those histories ripple through the movements.

These themes remain in "Nefés" (2003). But her work has also moved away from theater and more towards expressive movement. In this sense, the personalities of the dancers are internalized. Their histories are performed by movement more than through the more explicit means of storytelling we're usually accustomed to. Oddly, this pushes the work back in the direction of modern dance by returning to the rotating axis of the body. But it also, very subtly, gives the axis a complex and rich history of Pina herself and of her dancers as those histories ripple through the movements.Top photo by Stephanie Berger, NY Times

1 comment:

Hi im a dancer and i was wondering who and how old tho guys were in the sencond picture ther're so flexable and photogenic.

Post a Comment